Salon Polityki

Xawery Wolski: “Coming Back to the Roots”

Poland 2019

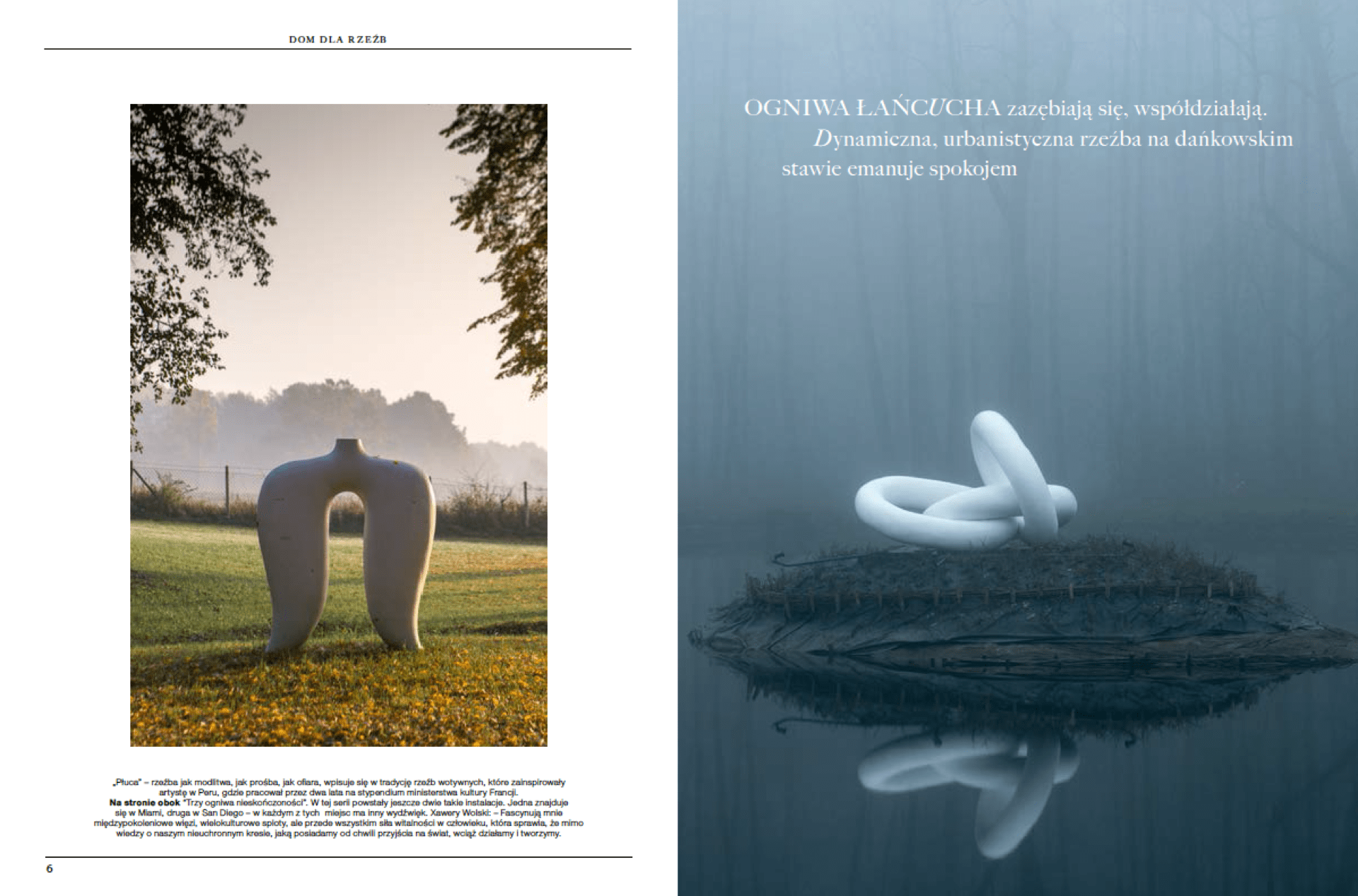

The article narrates the story of my ancestors who for four generations dedicated their lifes to science and nature. On their own land their practiced plant breeding and natural genetics in order to create new species of plants especially oats and rye. Their successful research was interrupted by the second world war when the estate was confiscated by the new communist regime that was installed in Poland. When the Berlin wall was torn down and the whole political system collapsed, my father was able to purchase Dankow back from the government. The estate was in terrible state, he started to restore it and died soon after in the same room in which he was born. Dankow is a small village surrounded by the biggest apple orchards of Europe situated one hour away from Warsaw. It stayed in abandon for years until I have finally decided to restore the old family house, the laboratory, the warehouses and the park.

Then the article tells briefly a story of my life as a journey that lasted over thirty years until I decided to ship from Mexico my sculptures in order to create a future foundation for international artists , a park of sculptures and a gallery with my art. There are gathered my early works which curiously were made of seeds and the Infinity Chain series that in this context take on an additional meaning of genetics and family union that continuous through generations. It is a place of peace and inspiration and hopefully I will have a pleasure to see you there some time soon.

Xawery

Arte Al Límite

Chile, 2019

Time sequences expressed through bronze

By Juan Pablo Casado. Bachelor in Hispanic Literature (Chile)

Xawery Wolski is a sculptor that works with the continuity and timelessness of art. His pieces bind the world together with large-scale chains installed in different sites and local backdrops. Through a repetition of elements, the Polish artist reveals the presence of volume and the continuity of time in the space.

Sometimes it’s the context that shapes the artist. Xawery Wolski, sculptor, was born in Poland in 1960, a time in which the communist regime only allowed for lifestyles that complied with the ideals of the ruling party. “For me, the only way of leading an independent and respectable life was to gain an artist status, which provided the opportunity to leave the country,” the artist assured. He decided to improve his skills in the Fine Arts Academy in Poland, where he studied graphic design.

His work, that had initially started off with painting and a bidimensional support, suddenly became filled with volume and space. This new path led him to his love for sculpture. “It was even harder to become independent through this path, because only the government and the Catholic Church commissioned sculptures, both of which had a very important role in my country,” Xawery recalled. In order to make a living, the sculptor had to leave his home country and emigrate to Paris. There, he studied at the Academie des Beaux Arts, where he continued developing his artistic practices under the tutelage of César Baldaccini.

He creates sculptures that follow the principle of multiplication and accumulation of elements. In Xawery’s own words, these pieces “represent a portion of the energy and time of a space that’s devoid of other meanings.” Time, one of the recurring elements in his work, is a concept he introduces into the pieces at an early stage, at the very heart of the creative process. For Wolski, this is evinced through the patience and faith that breathe life into every sculpture, to each piece that lives and is destined to linger on.

These are the defining expressive features of a style that is rooted in the movement of repetitive elements, bringing space and sculpture together. Every material, every country and every culture are presented as the spiritual agents behind each piece. On the other hand, the local backdrop that surrounds the piece adds a distinctive and meticulous touch. “The idea is to understand the complexity of historical, political and social backgrounds and work with the available materials, finding their connection to the site, so they acquire a universal meaning. In art, I like to deliver an immediate and straight-forward message. Simple in regards to shape, but complex nonetheless. In this sense, I took inspiration from Kasimir Malevich, who merged spirituality with art,” the Pole explained. “It’s important to see the piece from different angles, to identify the perfect location, to observe it, as if the environment magically became part of the sculpture.”

A Chained World

Infinity Chains is the name of a project that has kept Xawery Wolski busy for decades. Starting in 1988, the project breaks up a chain into several fragments, to later install them in different locations around the world, as if the fragments were one piece. The visual and material features of the work allow it to be effortlessly and organically integrated into the local backdrop.

For instance, a commission he did for the Cross Border Xpress in San Diego, USA, is a metaphor to the separation of Mexico and the United States. The piece, a part of Infinity Chains, is joined by another site specific installation conceived for Warsaw, Wolski’s native city, to which he returned after a 30-year absence. “It is very satisfying to see that a project I started 30 years ago hasn’t lost its relevance, but is growing stronger instead and continuing to develop as I envisioned it. I think the continuity and timelessness of an art piece is the most important thing,” Xawery comments. After over 3 decades of work, the artist is still expanding his reach, while he loudly voices his identity.

Shanghai International Arts Festival

Xawery Wolski at the Liu Haisu Museum in Shanghai.

China, 2015

The San Diego Union-Tribune Newspaper

United States, november, 2016

Art Forum

United States, january 30, 2013

Text by James Eischen

There is a section of Baja California’s US border that is so covered with wooden white crosses that the underlying barricade is practically invisible. Each handcrafted cruciform figure affixed to the iron panels memorializes a missing person––another soul lost during the daily attempts to cross over. Three new sculptures by Xawery Wolski, commissioned by the El Cubo contemporary art space, reflect on the grim phenomena of mass disappearance in Tijuana. Like a wayward traveler, Wolski has made a tumbleweed’s progress northward by picking up and transporting objects found along his own border-bound journey. The resulting works are fashioned from reclaimed terracotta or silicone––materials serving to highlight Mexico’s economy of artisanal craft making and unscrupulous production of luxury commodities. In Vestidos de silicona (Silicone Dresses), 2012, fifteen frocks hewn from resin sourced at a nearby factory waft inside a dark room. Accompanied by composer Ketil Bjørnstad’s somber overtures, the installation waxes funerary in its invocation of the numerous quinceañera dress shops lining this city’s streets and the multitudes of fallen youths that will be unable to fill them. A sculptural grouping outside, whose works date from between 2001 and 2012, emblematizes mortality and likens greater society’s weaknesses to the vulnerabilities of human anatomy––large dismembered limbs and organs appear as if excised from the building itself. In another room, Cruces V(Crosses V), 2012, conjures up that epitaphial border bulwark as seventy two unmarked crosses slip down from the wall and seep into the ground.

Art Nexus

Colombia, may, 2012

Text by Irina Leyva

Xawery Wolski established his residence in Mexico Cityin 1997, following the long standing tradition of European expatriate artists living in the country. He was born in 1960 in Warsaw, Poland, where he was educated at the Academy of Fine Arts. He also lived in Paris, where he attended the Academie des Beaux-Arts and the Institut des Hautes Etudes en Arts Plastiques; and in New York at the New York School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture. He later traveled to Carrara, Italy, where he was trained to master working with marble, thereby completing a comprehensive and classic education. Wolski also traveled to South America and Asia, spending time in both continents.

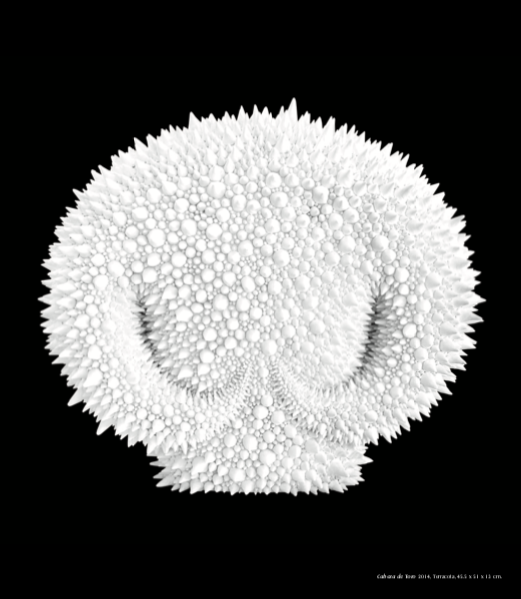

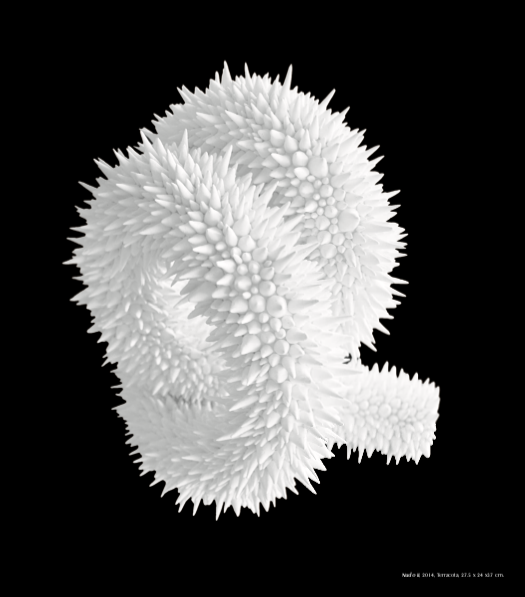

After receiving this type of education it is no surprise that he fell in love with the Mexican rich craft tradition; and soon enough his pieces started to show that influence, mostly by ‘borrowing’ technical aspects from it. Particularly visible in this exhibition, the artist presents a selection of pieces from a couple of series that he has been working on for at least the past two years. The diversity of the work, despite the fact that it was made during the same period, allows one to see a‘visual resume’ of this time, and his oeuvre in general. Through it we can see how his mind works and the subject matters that interest him; mostly, how he combined his classic background with the new techniques and themes.

The first piece that we see upon entering the exhibition space, Tzalan Blanco (White Tzalan), beautifully encapsulates this idea of integration to his new environment. The elaborate rows of small beads create a flowing cascade that evokes a ritual dress, all in white. Made of terracotta, silk thread and acrylic, Wolski created what seems like a ceremonial gown, showing the visual and conceptual influence of anthropological objects. The title is a tribute to the Nahualt people and a direct reference to their textiles. By selecting it Wolski shows his assimilation of the culture and his understanding of the place.

Religion, especially Catholicism, has been an integral part of daily life in Mexico, and Wolski‘s Círculos (Circles) series are inspired by rosaries, commonly used for praying. These detailed renderings are made of perfectly round pieces of individual terracotta beads flawlessly aligned. The endless circles allude to the intimate process of praying, connecting time in an infinite ritual cadence. The color selection in this series is also inspired by the traditional red used in liturgical ceremonies. Wolski’s use of color and the attractive textures makes these pieces very appealing.

Another series that he has been working on for a while, and that may be the most recognized of all his oeuvre,are his white terracotta chains. Placed as an installation in a room of its own, the thick chains hang from the ceiling and create a sort of ‘white forest’. From far away the chains seem ordinary, but upon close inspection we realize they are made them from clay and not from metal, as anticipated. One of these works is part of the Rufino Tamayo Museum collection in Mexico City, and is currently on exhibition as well.

Perhaps the most attractive piece in this exhibition is Globos (Balloons), a delicate and seemly fragile installation consisting ofan arrangement of crocheted fine wire structures. The composition reminds us of floating lanterns, an effect that is reinforced by the display, set against a dark wall.

There is a theatrical intention in the way he presents his works, and a tendency to use duplication as a way of structuring them. This pattern is clear in his installations, in which he uses the effect of repeating elements in a consistent manner. Although even the works that are not installations per ses how this tendency, it is on the second where this rule is more evident. A good example of this statement is Constelación (Constellation), his interpretation of a starry night in white. The stars are represented by hundreds of terracotta balls, all seemingly perfect from far, in an imitated uniformity. Up close we can see that each ‘star’ was individually made, therefore the intentional imperfections.

He is not afraid to experiment, and tries his hands on different materials such as clay and metals, creating beautiful renderings of objects made in trompe l’oeil effects, like the chains and his interpretations of textiles. He can be bold when selecting his palette, going from a spectrum of subtle combinations of different whites to a daring red.

Wolski’s work is time-consuming by nature and by the fact that he uses traditional techniques. This apparently naive deed makes possible the daunting confluence of past and present, and the juxtaposition of many cultures he has experienced in his life. His perception of time and his appreciation of history allow him to combine elements from Pre-Columbian civilizations with contemporary themes. Looking at his works we can see reminiscences of anthropologic and ritual objects integrated in his organic forms.

There is something spiritually inapprehensible in his works, a hidden narrative that comes alive upon reexamination of the pieces. His vision of art is cosmopolitan, deterred by time, space or geographic location. Through his art Wolski brings us his vision of life filtered by his vast, vital experience.

LA Times

Nature of universal truths is dusted off and explored

United States, may, 2012

Text by Holly Myers

The title of Polish-born, Mexico-based artist Xawery Wolski’s current exhibition in the Ben Maltz Gallery at Otis College of Art and Design is a single, proverbially elemental term translated into three languages: “Polvo/Proch/Dust.” In a show populated largely by terra cotta sculptures, it comes as a droll reminder of art’s intrinsic ephemerality, and a sober allusion to the mortality of the body itself, recalling God’s famous pronouncement to the fallen Adam and Eve in the third chapter of Genesis: “For dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.”

The multiple translations Wolski provides of this title refer to his own cosmopolitan background, yet also imply a sort of ominous universality. The natural cycle of creation, growth and disintegration is, after all, absolute. With this in mind, Wolski appears to be making the most of it, sublimating his materials (glazed terra cotta primarily, but also paper, wire and bronze) into truly elegant objects. The only dust found here probably blew in from the outside; the works themselves, all less than 10 years old and clearly well cared for — are nowhere near to crumbling. Nor is it the drama of disintegration — central to the work of many environmental artists, for example — that seems to interest him. Rather, one senses, it is the illusion of stability that flawless fabrication can inspire.

Predominantly white in its palette and beautifully installed, the exhibition is a pleasure to move through. Pale tones and sumptuous textures create a calming atmosphere and the objects mingle harmoniously, commanding every region of the gallery. The terra cotta pieces are large, stylized forms with clean lines and smooth, eggshell-colored surfaces. One consists of five cloud-like rings, suspended from wires at various levels around the gallery; another, a fat, 60-link chain that snakes menacingly across the floor. “Retablos” (Reliquaries) (1994-97) is a grid of 40 identical, wall-mounted boxes, all eerily empty, and “Frutos” (Fruits) (2002) is a ceiling-to-floor vine covered in 600 tiny bulbs resembling crook necked summer squash. Though cool and rather slick from a distance, these pieces soften considerably at close range, where the warmth of their burnished surfaces can be fully appreciated (though, sadly, not touched).

Wolski’s skill in handling the terra cotta is evident in the illusion of lightness he manages to bestow upon the objects. The hovering of the clouds appears quite effortless; the chain looks as though it might easily be kicked aside. Even in the show’s one bronze piece — a pair of free-standing spherical knots painted to look exactly like the terra cotta — he achieves a quality of veritable buoyancy.

It is in his one wire and two paper works, however, that a real sense of delicacy emerges. The former consists of several dozen roughly 16-foot chains made from what must be thousands of tiny, copper wire rings, all clearly handcrafted, hanging in a large, U-shaped cluster on the wall. The precarious insubstantiality of the piece is almost titillating; one heavy hand could easily crush it. Equally diaphanous in tone is a series of eight chalky gray photographs, each portraying what appears at first to be a few thin cracks but are actually slender lines of ocean surf, viewed from high above.

The second work on paper — titled “Tatuajes” (Tattoos) (1997-2001) — makes very different use of the medium. Here, rather than printing or drawing across the paper, Wolski essentially sculpts it using the tip of a needle, occasionally puncturing but more often indenting gently to create tiny fields of gravelly texture. There are six individual “drawings,” all abstract and all quite small, and they are perhaps the most purely beautiful objects in the show. Less memorable is a piece called “Carta de Amor” (Love Letter) (1998), which consists of 259 individually lettered tiles arranged to relate (in English) the lament of an abandoned lover. Conceptual rigor does not appear to be Wolski’s strong suit generally, and the shortcoming is especially evident here.

The only piece to notably depart from the general white-on-white scheme is “Vestido” (Dress) (2000), a draping garment made from tiny, black terra cotta beads. Displayed against a wall as if suspended from a coat hanger, the piece has an unsettlingly penitential feel that brings one back to the Catholic undertones of the show’s title.

If the terra cotta clouds, the copper-wire chains or the “tattooed” sheets of paper might be said to represent a sort of material perfection, then this object — dark, heavy, dull in texture and presumably very uncomfortable — would seem to embody the converse denial. Though constructed with the same skill as every other piece, “Vestido” functions as the show’s shadow side, a reminder of the disintegration that eventually follows creation. With its small, unpolished beads, its suggestions of darkness and its ominous weight, it appears one step closer to dust.

Arte al Límite

The Endless Return

Chile, 2014

Text by María Fernanda Reyes Retana

Xawery Wolski (Warsaw, Poland, 1960) has spent over thirty years going over a single idea, a question, an absence. He left Poland at twenty-three years old, claiming to have studied in Perugia, Italy, where he never arrived, instead beginning a journey of endless returns. By María Fernanda Reyes Retama. Writer (Mexico). If, in all that you will to do, you begin by asking yourself: “¿Is it certain that I will to do it an infinite number of times?” this would be your most solidcenter of gravity Friedrich Nietzschee Began in Paris, at the academy of fine arts, where he could continue his training on sculpting and drawing, already begun in Poland. The construction of one of his first clay chains, in a brick factory, is something that she remembers from that century and the contradiction of the hard life of the workers among the infinite boilers, that despite belonging in a “free” country, they seemed to be tied to that tiring, monotonous reality. His first stay in that country didn’t last long and he began to travel around the world. The United States, New York of the 80s, was another place that marked his way. As a boy who was raised in a communist society, he was astonished by the exuberance and maybe also the vanity of the artistic world of the time, when the most important thing was to look good, stand out and of course, possess. He returned to Europe, but this time he did arrive to Italy, to Carrara, to study sculpting, working with marble in the classic fashion. His first trip ended on returning to France, where he now took more time to finish his studies, teach classes, and with this came scholarships and opportunities to go places and practice his skills. The sculptures of Xawery Wolski have a certain harmony that defines them; the majority sustained by smooth, curved, silent lines. Even the crosses or straight figures are curved some. He has never left the chains: of mud, of wood, white chains that don’t imprison, links that intertwine and that, motivated by the strength of their unity, pass through walls, shorten distances. White chains that lie sleeping or hang inanimately. Chains of mud, material that Xawery assures, “contains the memory”.Chains that are piled up, fastened together and define themselves; fragile in nature and powerful due to the relentless repetition.

They utilize space…”With the opening of Poland’s borders, Xawery has begun his return home, though he remarks: “I don’t know if one really returns. One arrives to another time, everything has changed”. Presently he lives partly in Warsaw and partly in Mexico… and he continues to travel around, to Asia, to America. Human torsos upholstered with thorns that appear to emerge aggressive and reborn, determined to exist again. The spines are made from old bread, dry bread; the bread that is thrown out in restaurants or bakeries in the city, but Wolski uses them evoking the rations that prisoners inPoland were given in World War II. “They were miniscule”, he still affirms with compassion. Dirt, stone, seeds, bread, wood. In Xawery Wolski’s piece the materials and neutral or solid colors are as pivotal as the material itself. They have a lot to do with the origin, the source, which doesn’t change. Nevertheless, to complete his work, he doesn’t stay in one place. He travels in the cluster of elements available in our time, like silicone, glass, advertising panels, which everway he’s going, power up for it and keep walking, to keep turning on this journey of affirmations, changes of perspective, growth…this journey of endless returns.

La Revista

Memory, Body and Clay

Mexico, 2014

Text by Pamela Olavarría

THE MINIMALIST AND ORGANIC SCULPTURES OF THIS ARTIST ARE INTERLACED WITH TRADITIONS, CREATING NEW SPACES AND CULTURAL CONTEXTS WHICH ARE BASED IN THE RELATIONSHIP WITH EARTH AND SPIRITUALITY.

Wolski, the Warsaw bom visual artist (1960) is currently living and working in Mexico City and New York. His work evokes the body and its anthropological origins, directly lir1ked to earth.

What issues are you interested in revealing through your work?

Being alive, facing simultaneously the multiple experiences which life is constantly bringing us, without interruption. The essential questions seem to arise from this experience and allow us to work at a level of exaltation, more transcendent. We are conditioned to live in a temporary space, and from this point of view, my work takes a diversity of shapes, trying not to get attached to the same material solutions, it holds an infinity of possibilities which allows it to be modified according to its function in the environment it is in.

Your works arise from the investigation of memory and the body, and are embodìed in the simplicity of clay. Can you tell me about the process which bìnds these three fundamental ideas?

In its anthropological Origins, the body is directly linked to the earth. Earth is an unlimited material which evokes consistency. All of us have a relationship with it, even if it’s hidden, and it does not matter if our daily lives are apparently distant from it. My work is to remove the object from the immanence of what is useful: allowing an erL1ption in the consciousness, and through this allowing us to experience art, what is ritual and what is sacred. _ _ Earth has a memory in itself; everything returns to her, including us.

When we define the limits of art; what do you think is the difference between a work of craft and the production of a work of art?

Handicrafts are created by sculptors, magicians, without names, titles or signatures, without any given values, no egos; consolidated by the proof of time, they speak for themselves, they maintain their own aesthetic message. So, when you remove an object from the immanence of what is useful, that is, sacrifice, it takes us to an artistic creation. It is an internal process.

It seems to me that there is an interesting “hybridisation of Canclini” in your production, since you create on the base of intercultural relationships, which allows you to take them as your own and have access to different socio-cultural circles.

During my life I have experienced moves to different places, countries, continents. Iwas born in Poland, and at the time under the communist regime, I decided to leave and continue my studies at the Academie des Beaux Arts in Paris, I worked sculpting marble in Carrara, Italy; then furthered my studies in New York. The greatest experience was arriving in Latin America, where my work took a new turn, inspired by a new understanding of light and space. ln Peru, I dedicated myself to studying the ancient techniques of the use of clay in pottery and in architecture. Finally I moved to Mexico where I was able to carry on with my investigation, inspired by the Mesoamerican culture.

Regarding “La Cortina” (1993) Fernando Castro Flores mentions a “Veil Function” suggesting a symbolic relationship between the artistic product and the imaginary plane. Tell me about this veil.

I work based on the idea that new places and new cultural contexts allow you to become free from the structure as well as of our personal history. A work of art can change its sense due to the cultural context and the same object can be enriched by new influences. ln our bodies, we carry part of the history of every place we visit, we breathe it, and we assirnilate it, it becomes part of our memory: there is always more, it is never enough, it is always possible to go further, this is the veil that separates us.

Antonio Zaya suggests that in your work, you theorize about your own creation, thus satisfying the curiosity of the critics. In which way do you think this passes on to the spectator?

In my last exhibition entitled Mrok (” dark light” in Polish) which is currently being exhibited at the Museum Of Modern Arts in Mexico City, I decided to put just one piece, to which we added audio with an abstract text which talks about the mystery of the body. I feel that when I listen to my voice reciting these phrases which are abstract and solemn, it enriches and puts out of focus the view of the spectator and this way, both the work and the space are held by its complexity. lt is obvious that this cloud of twisted wires speaks for itself, it does not need the support of the text, but because we all come from different places, we try to understand each other better, including in this interview.

And what are your next projects?

Every day I am more interested in what is tangible, in what is fragile and mobile. My next work is related to three works created in Asia, where I had the opportunity to work with raw silk, recycled and fired as if it was clay, together with another two exhibitions which will be presented in Warsaw in September.